Research

I studied the evolutionary molecular and epidemiological dynamics of viral diseases affecting the human population on a global scale, and how to implement a new class of evolutionary models which account for incorporing insertion and deletions events into phylogenetic reconstruction.

Algorithms for optimising binary tree topologies

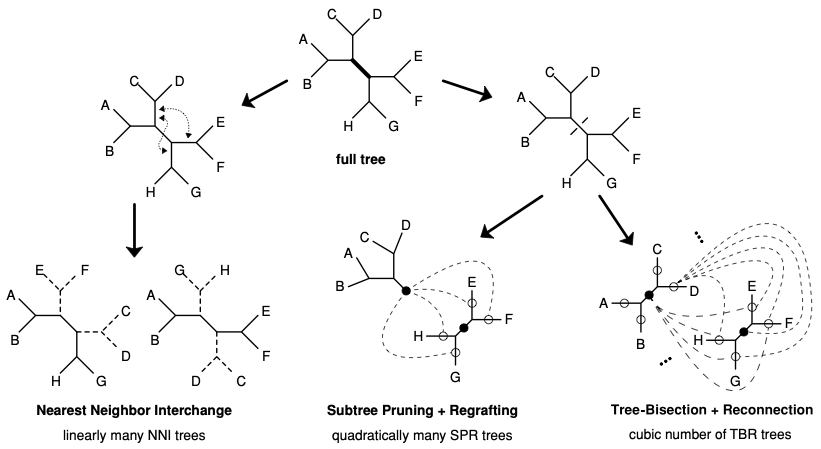

The tree topology is a multidimensional parameter that requires a specific class of algorithms for its optimization. Since exploring the tree space is a highly computationally demanding step, we use the Unified Tree Search Heuristics C++ Library (TSHLib), a phylogenetic library optimised for fast tree-search that supports multi-core parallelization. We tuned the tree-search acting at several levels: proposing algorithm, tree-space coverage, node seeding methods. To compute a tree rearrangement we implemented two proposing algorithms: a fast node-swap and a more computationally demanding node-cut methods. Both these two methological classes are well established in the community, and their computational limits have been widely studied.

|

|---|

| The three standard tree rearrangement operations (NNI, SPR, and TBR). The three basic tree rearrangement operations (NNI, SPR, and TBR). In SPR and TBR all pairs of ``circled’’ branches among the two subtrees will be connected (dashed lines), except the two filled circles to each other, since this yields the full tree again |

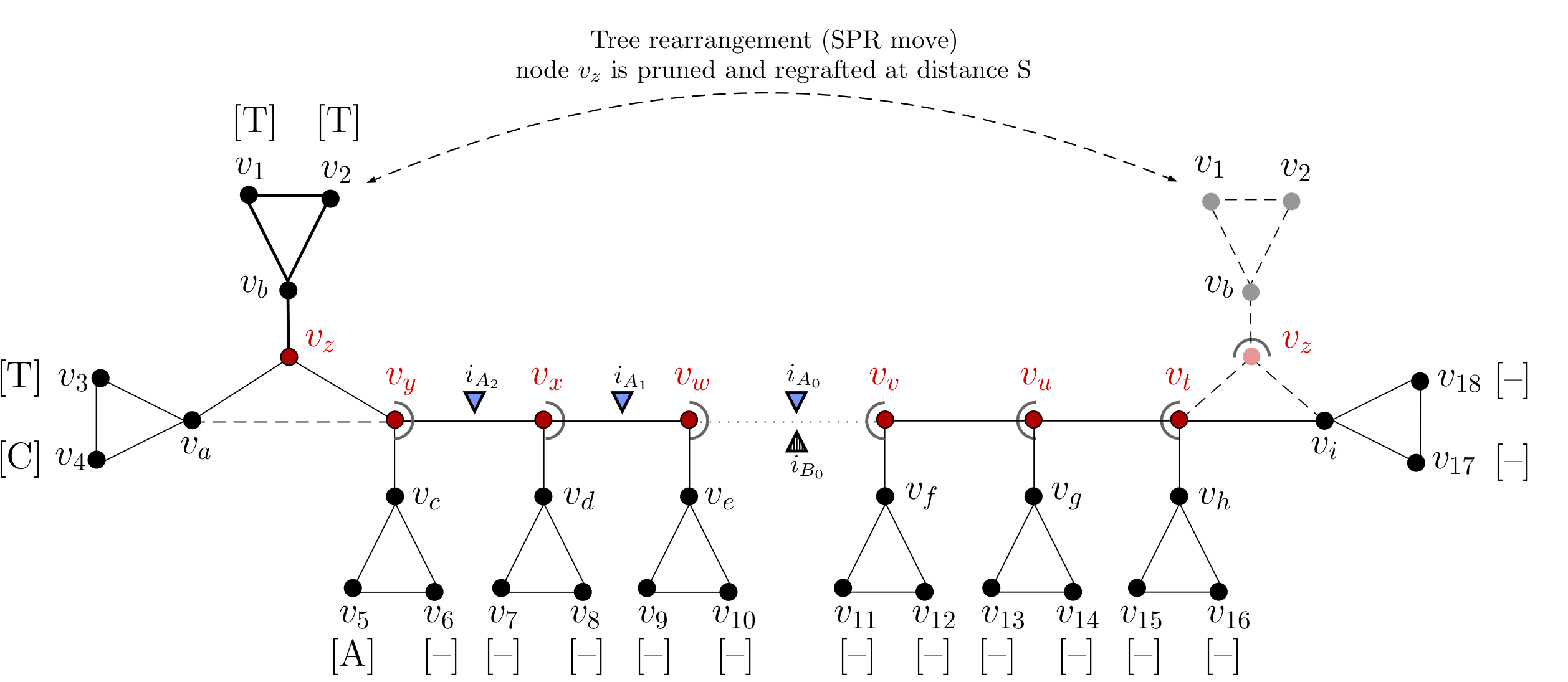

In our implementation, at the beginning of the tree-search cycle, the tree-search algorithm proceeds by proposing a set of rearrangements on the current tree. The algorithm searches for all the possible non-redundant rearrangements within a radius distance \(d\) from either all the available nodes on the tree-topology (greedy), or from a random subset (random-hillclimbing). The radius distance \(d\) is automatically set such as NNI moves will target only the nearest neighbours nodes and SPR moves the remaining far more distant ones, respectively. The likelihood of every new tree is re-computed using a conservative approach: only the likelhood matrices pertaining to the nodes upwards (towards the root) from where the rearrangement occurred will have to be re-computed. In this manner, the re-computation is restricted only to those likelhood matrices where it is strictly necessary, and the likelhood matrices of the nodes not included in this set are fully recycled. The computation occurring for an NNI move is a special case of an SPR move. The process is shown in details in the figure below.

|

|---|

| Recomputing the multi-set of insertion events during the tree-search optimisation. For a rooted tree topology there are multiple evolutionary scenarios which explain the pattern of gaps and characters observed at a particular multi-sequence alignment (MSA) site. The figure illustrates the re-computation of the multi-set of insertion events during tree-search optimisation for a global tree rearrangement (SPR move). This tree is rooted on node \((v_{\omega})\), and has 16 internal nodes \((v_a,v_b,v_c,v_d,v_e,v_f,v_g,v_h,v_z,v_y,v_x,v_x, v_w, v_v, v_u, v_t, v_z)\) and 18 leaves \((v_{1,\cdots,}v_{18})\). The tree represents the phylogeny of a single site (or column of the MSA), \(s_i=\{v_1:(T);v_2:(T);v_3:(T);v_4:(C);v_5:(A);v_{6,\cdots,18}:(-)\}\). At the indicated site, the subtree indicated in bold is pruned at node \(v_z\) and regrafted between nodes \(v_t\) and \(v_i\) at a distance \(S\). Nodes \(v_a\) (orphan) and \(v_y\) (step-parent) are reconnected, and at the regraft site, the connection between nodes \(v_t\) and \(v_i\) is broken. Nodes in the rearrangement path (coloured in red) \(\{v_z,v_y,v_x,v_w,v_t,\ldots,v_u,v_v,\ldots,\Omega\}\), with \(\Omega\) being the root of the tree, must update the multi-set of insertion events \((i)\), here indicated by triangles. Before tree rearrangement (blue triangles) the multi-set of insertion events leading to the observed characters is: \(i_A = \{i_{A_0}; i_{A_1}; i_{A_2}\}\), and after tree rearrangement (dashed triangles) is updated into: \(i_B = \{i_{B_0}\}\) |

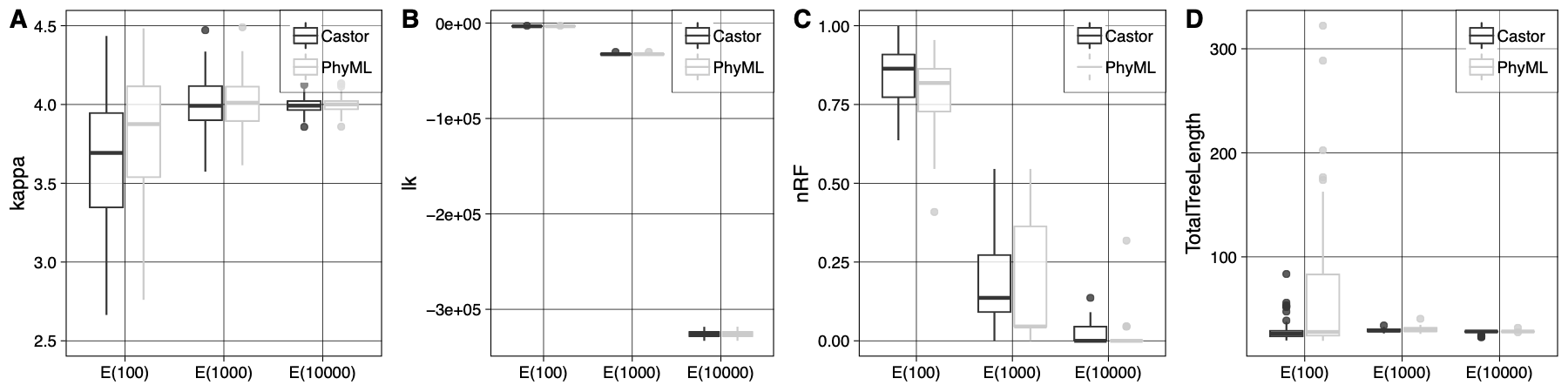

We tested the soundness of our implementation’s tree-search algorithms by comparing the tree topologies inferred by Castor with those inferred by other softwares (i.e. codonPhyML). With increasing number of sites in the alignments both Castor and CodonPhyML eventually find the true tree on average. It is important here to notice that the variance of the estimates inferred by Castor and CodonPhyML is due to the distance-based initial trees. Lastly, we repeated this test, but this time inferring the tree topology under the true indel-aware substitution model (K80+PIP). We were able to recover the true value for all the numerical parameters and the true tree topology.

|

|---|

| Benchmark tree-search algorithms: Comparison of tree-search accuracy under indel-aware substitution models for increasing data volumes using Castor and codonPhyML. A) Value estimates of the kappa parameter inferred from data set A2 (generated under K80) under the traditional substitution model K80 implemented in Castor and codonPhyML (denoted Castor and PhyML in the inset, respectively). The initial bioNJ tree topology is optimized using NNI moves. The boxes and whiskers are computed from 100 estimates per data set (shown on x-axis). Inferences are obtained from data of increasing expected length (100, 1000, 1000 sites). B) is analogous to A), with only the log-likelihoods estimates. C) and D) are analogous to A), but showing the nRF measure between inferred trees and the true tree used to generate the data, and total tree lengths inferred by each program. |

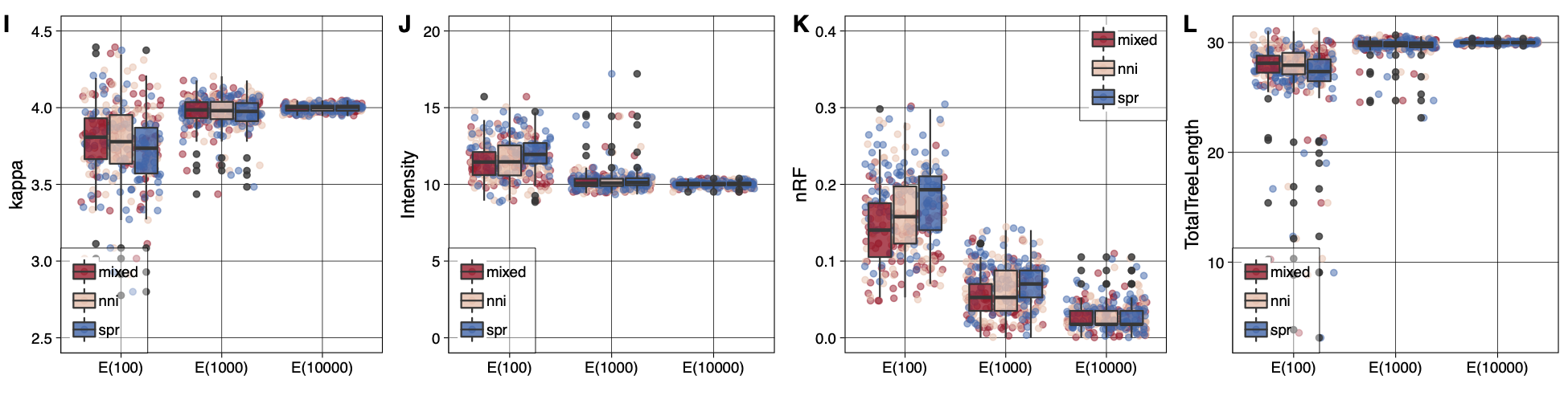

After proving that our implementation is sound, we moved forward with testing the asymptotic convergence of the ML estimates under indel-aware substitution models. The figure below shows that with increasing number of sites in the alignments, both the numerical parameter estimates and the tree topology asymptotically converge to their true values (panels I-L for 60 taxa). As expected, the variance around all the numerical parameter estimates diminishes with the increasing the alignment sites, as well as the tree topology distance from the true tree. It is worth noticing that already for small datasets, using a mixed tree-search strategy, the estimates of both numerical parameters and tree topology were already close to their true values. We therefore suggest the use of this option in real case studies.

|

|---|

| Asymptotic convergence of numerical model parameters and tree topology under the true model using different tree-search strategies. An initial bioNJ tree topology is optimized using either NNI, SPR, or Mixed moves (denoted in the inset as nni, spr, mixed), while four parameters are monitored: the substitution parameter of the K80 model – \(\kappa\) –; the intensity of the PIP process – \(I\) – ; the measure between inferred trees and the true tree used to generate the data – nRF –; and the total tree length. The boxes and whiskers are computed from 100 estimates per data set (shown on x-axis). Inferences are obtained from data of increasing expected length (100, 1000, 1000 sites). |

In Castor – a new phylogenetic Maximum Likelihood inference software which adds the PIP model as an extension to the most common traditional substitution models – we incorporated well-established tree inference methods (see above) into a framework for indel-aware phylogenetic inference. This software solution is based on the Bio++ Bioinformatics Libraries (Dutheil and Bigot, 2018) and inspired by the bppML module of the BppSuite programs for phylogenetic and sequence analysis. To boost computational time and memory allocation performances by better harnessing of modern CPU architectures, we built the framework, algorithms, and data-structures using C++ Object Oriented Programming (OOP) design patterns, taking advantage of code vectorisation and multithread paradigms.

Grants

- 1 Feb 2018 - 31 Jan 2019: University of Zürich - Forschungskredit Candoc grant no. K-74409-01-01

- 1 July 2015: UZH-ETH MLS Travel grant

Teaching

- GENECO course - Computational Molecular Evolution: Detecting Positive Selection - at University of Lund

- Frontiers in Plant Sciences 2016: Phd course in protein-coding evolution and detecting natural selection

- ZHAW-SIB Summer School GEMP 2015: Genomics and Evolution of Microbial Pathogens

Publications

-

Lorenzo Gatti, Jitao David Zhang, Maria Anisimova, Martin Schutten, Albert Osterhaus, Erhard van der Vries, Cross-reactive immunity drives global oscillation and opposed alternation patterns of seasonal influenza A viruses, BioRxiv (2017) doi:10.1101/bioRxiv/226613

-

Davide Heller, Andreas Hoppe, Simon Restrepo, Lorenzo Gatti, Alexander L. Tournier, Nicolas Tapon, Konrad Basler, and Yanlan Mao (2016). EpiTools: An Open-Source Image Analysis Toolkit for Quantifying Epithelial Growth Dynamics. Developmental Cell 36 (1) (January): 103–116. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2015.12.012

-

SIB members, including: Anisimova, Maria; Gatti, Lorenzo; Gil, Manuel (2015). The SIB Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics’ resources: focus on curated databases. In: Nucleic Acids Research. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1310.

Software

- Castor. Indel-Aware Phylogenetic Tree Inference Software

- Castor AWS. Auto-scaling On-Demand Indel-Aware Phylogenetic Tree Inference on the public cloud

- Tree Search Heuristic Library. The Unified Tree-Search Heuristic C++ Library (TSH-LIB) is a new unified implementation of binary tree topological searching engines for phylogenetic analyses.

- AliSt. ALIgnment STatistic, a program to compute indel presence statistics on Multi-Sequence Alignments.

- NetXDiscreteDynamics. Probabilistic framework for discrete evolutionary dynamic

- Phylo-Tools. Phylogenetic tree manipulation toolbox

- Epitools. Image processing software for Epithelial Tissues